Our inability to grasp the danger of non-resilient systems – to which anthropogenic climate change represents one of the greatest threats – will only worsen the impact of such changes when they arrive. This short-termist thinking, Carney contended, not only represents a social and environmental threat, but also exacerbates the cost of mitigating these threats.

GFI Report: Assessing the Materiality of Nature-Related Financial Risks for the UK

The groundbreaking report from the Green Finance Institute both consolidates and confirms this logic. The headline finding is that damage to the natural environment is slowing the UK economy, and, in a worst-case scenario, could lead to an estimated 12% reduction in GDP in the coming years – larger than the hit to GDP from the global financial crisis or Covid-19. In its analysis, the report models three scenarios, with impact assessed against GDP and the lending portfolios of the UK’s largest banks. Importantly, it incorporates an understanding that nature and climate risks are cumulative; once certain tipping points are crossed, a process called ‘locking-in’ occurs whereby the impacts may become essentially irreversible. The authors highlight ‘chronic’ (ongoing) risks, such as soil decline, and ‘acute’ risks (sudden shocks), such as a pandemic. When the two are combined, the socioeconomic effects are naturally compounded.

Report scenarios: Domestic and international

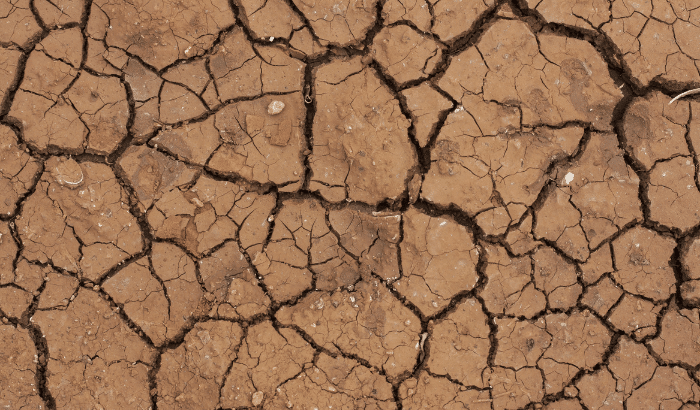

The GFI report discusses a domestic (UK) scenario, which combines the chronic risks of soil health decline, water pollution and scarcity, air pollution and biodiversity loss with the acute shock of wildfires, heatwaves and drought. A second, international scenario demonstrates the chronic risks of water quality and scarcity, soil health, pollinator decline, fishery overexploitation, and biofuel-land use tensions and fiscal issues, and how they interact with the failure of multiple global ‘breadbasket’ countries (key staple food exporters), geopolitical instability, and trade wars. This stresses the interrelated nature of the UK economy and global food supply chains. Thirdly, they model a zoonotic pandemic scenario, assessing how increased antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and outbreaks of livestock and poultry disease could result in a global pandemic and lockdown.

Across the three scenarios, economic growth invariably slows. By the late 2020s, GDP is exposed to a £35bn-£70bn erosion. As of 2030 when ‘acute’ factors are added, this loss increases to £140bn in the first two scenarios, and up to £300bn when the pandemic scenario is accounted for. In short, the report demonstrates the inextricable link between climate change, the natural environment and the economy. It seeks to combat a lack of action around valuing the role that nature plays in humanity’s socio-economic foundations. Whilst the private sector has started to mobilise toward finally recognising, if not mitigating, climate change, the opposite is true for the natural environment. Moving financial flows away from harmful practices is thus one of the principal challenges we now face.

Summarising this in the report’s foreword, Helen Avery, GFI’s Director of Nature Programmes writes, “We must first stop treating nature and climate as separate. Even to regard climate and nature as ‘two sides of the same coin’ does not do justice to their interrelatedness. Indeed, the report shows that to disconnect the risks posed by the interactions between the two would be perilous”.

Climate risk is nature risk, and vice versa.

GFI Report review

In no uncertain terms, then, the research calls for a drastic programme of change across policy and praxis, from government through to financial institutions. Letting material impacts on nature (and thus its relationship to financial resilience) slip through the cracks, they argue, now represents negligence that society can ill afford. The UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, meaning that those aspiring for a thriving economy must also aspire for a thriving natural environment. By sector, agriculture is at particular risk of exposure. Meaningful change, not lip service, is the only viable way forward.

Perhaps where the report falls short, however, is questioning where GDP as a metric fundamentally sits in the equation. It doesn’t value human well-being (which, as the report shows, is intrinsically linked to the environment), fails to value ‘hidden’ labour, and is predicated on extracting (or at least chronically undervaluing) natural resources. Scholarship calling for alternative economic framings such as Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut Economics’ or the work of Jason Hickel seeks to question precisely these flaws. Nonetheless, the call for the economy to properly value nature (insofar as this is possible in financial terms), and respect planetary boundaries, should not be dismissed.

If the relationship between GDP and nature continues on its current trajectory, where we pretend that ‘risk’ remains confined to societies, geopolitics and nations, rather than the way these structures intentionally degrade the resource base which supports them, then the economy declines, and prosperity with it. “The broad and correlated nature of these risks” the report highlights, shows that nature-related risk represents a material threat to the financial stability of the UK. The findings ought to be heeded by policymakers, and fast. The twin crises of climate and biodiversity must now both be defining economic issues.

To return to Carney, one line is particularly striking. “Once climate change becomes a defining issue for financial stability, it may already be too late”. As this report gains traction, we can only hope Carney’s warning has not already come to pass.

You can read the full report on the GFI website, here.